레오나르도 다 빈치의 작품이라고 전해지는

"구세주 Salvator Mundi"가

사상 최고가 4억 5천만불이란 천문학적 가격으로

11월 15일 밤 뉴욕 크리스티 경매에서 팔렸습니다.

곧 위작이라는 전문가 주장이 뒤따랐습니다.

영국 가디언지는11월 16일

레오나르도 다 빈치의 全작품 14점('구세주' 포함)을 싣고

'구세주'가 위작인가 여부에 대한 자신의 의견과 함께

각 작품에 대한 간략한 설명을 실었습니다.

과연 '구세주'가 진품인지 위작인지,

레오나르도의 다른 작품들과 비교해 판단해 보시길 바랍니다.

작품제목 오른쪽 숫자는 제작연도입니다.

여기 그대로 옮겨 싣습니다.

[guardian]

Leonardo da Vinci

All the Da Vincis in the world: rated

As Salvator Mundi, his potent depiction of Christ, becomes the most expensive artwork ever, here’s our guide to every Leonardo painting in existence, from the masterpieces to the less-than-perfects

Thursday 16 November 2017 14.43 GMT

Phallic남근 finger … Leonardo’s homoerotic동성애 St John the Baptist. Photograph: Alamy

The Annunciation (1472)

Photograph: Francesco Bellini/AP

On display at the Uffizi, Florence

In this dazzling performance, created when he was about 20 years old, we peer directly into the riches of Leonardo da Vinci’s mind. It has always been in Florence and, even though it was not mentioned by Vasari in the biography of Leonardo he published there in 1550, no one has ever doubted it’s by him. That’s because every detail screams, or rather softly sings, his authorship: the typically soft and dreamy view of mountains in the background, the lovingly detailed trees and flowers, the enigmatically불가사의 shaded, opulent호화 draperies직물 that cover the legs of Mary and the angel. Most of all, the wings of the angel are are given an astonishing amount of attention, more than any other artist would have. They are the first sign of Leonardo’s fascination with the dream of human flight.

Ginevra de’ Benci (1474-78)

Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

The juniper노간주나무 bush that frames this beautiful face like a dark halo is one of the clues that convinced art historians it is the same portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci by Leonardo that 16th-century writers mention, for juniper is “ginepro” in Italian, making the tree a symbolic pun말재간 on her name. Anyway, no other Italian artist at this time was painting women in this direct, characterful way. The melancholy mystery of her expression, the shadows that subtly미묘 define her features and, most of all, the exquisite realism of her translucent반투명 eyes and pink lips close up make this portrait a trial run for all his later ones. This was one of Leonardo’s most famous pictures in Florence, so when he returned there in the early 1500s, it’s no wonder he was commissioned to paint the Mona Lisa.

The Adoration of the Magi동방박사 (1481)

Photograph: Getty Images/Art Images

Uffizi, Florence

Leonardo left Florence in the early 1480s to become court artist in Milan, and never finished this incredibly ambitious painting. Paradoxically, its sketchy nature reveals some of his defining characteristics as a painter – slowness, intellectualism, hesitance. It also reveals the scope and vastness of his imagination in its images of wondrous broken architecture, horsemen fighting on a distant plain, and the hollow eyes of the Magi who look like they’ve seen too much. We see the real Leonardo here, a thinker, whose use of softly suggestive암시적 techniques and intense juxtapositions병치竝置 of the human and natural are ultimately expressions of his dream of capturing the whole of the cosmos in a painting. Funnily enough, this unfinished picture gets him closest to that vision. It seems infinite.

The Virgin of the Rocks (1st version) (1483-85)

Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Louvre, Paris

Here we see another aspect of Leonardo’s personality coming through: heresy이단異端. Was he, as Vasari wrote in 1550, “so heretical that he believed in no god whatsoever”? He certainly plays fast and loose with Christian convention in this peculiar, almost cryptic수수께끼 vision. There was no tradition of painting Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist in a rocky grotto동굴. It’s his invention. Even without its well-documented history and the sketches for it among his drawings, no one else could have invented that surreal geological landscape that he surely painted using the method he describes in his notebooks – staring at marks on a wall until you start to see bizarre faces, battles and landscapes. Yet he went too far. Mary has her arm around John the Baptist, not Jesus and the angel also points a long finger at John. The painting’s clerical sponsors rejected this mysterious attempt to sideline제껴놓다 Christ. Although it is in poor condition, ever detail has Leonardo’s supersentive touch.

Portrait of a Musician (1486-87)

Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Ambrosiana Gallery, Milan

The eyes have it. Leonardo didn’t just paint eyes. He studied them scientifically. In his notebooks there are studies of how we see and anatomical drawings of how the eye is connected to the brain. The big, brown eyes of this youth are quintessential정수精粹 examples of both his scientific view of human beings, and his incomparably subtle신비 painterly genius. The youth’s lovely curls are also a direct piece of self-expresssion, if Leonardo’s first biographer is to be believed. In 1550, Vasari wrote that Leonardo loved beautiful young men with long ringlets, just like this musician’s. There is no mistaking these archetypal전형典型 traits of Leonardo’s in this portrait. Equally, there’s no ignoring the comparative ordinariness of other parts of the painting – such as his tunic, which must have either been painted very carelessly or finished by an assistant.

Saint Jerome (c.1488-90)

Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Picture Gallery, Vatican Museums

Everything about this is truly Leonardoesque, including the fact he never got round to짬을 내다 finishing it. The desperate face of the self-tortured saint looks like it has been flayed박피 by an anatomist: Jerome’s taut팽팽 tendons힘줄 and exposed arteries동맥 and bones are extemely similar to Leonardo’s drawings of dissected절개 human heads and necks. Leonardo’s dreamy rocks and distant mountains once again make it look as if he used his surrealistic method of staring at stained walls until he started seeing things. No other artist in the 15th century left paintings unfinished like this, and no one would have kept such scraps anyway. Leonardo is asserting something in this unfinished work: that he is a genius, and his tentative sketches are worth more than anyone else’s finished masterpiece. More than 500 years later, that aura remains staggeringly bankable.

Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (The Lady with an Ermine) (1489-90)

Photograph: De Agostini/Getty Images

The Czartoryskich Museum, Krakow

Leonardo got on well with사이좋게 지내다 women, from Isabella d’Este, ruler of Mantua, to Lisa del Giocondo, model for the Mona Lisa, who he’s said to have entertained with musicians and jokes while she posed. In this portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, the lover of his boss Ludovico Sforza, he conveys her energy and free spirit in a portrait that has no equal in 15th century images of women. She seems barely contained by the picture, about to walk or run out of the frame. The pet in her arms is just as restless. This squirming꼼지락대다 creature was a heraldic emblem of Ludovico himself so Cecilia is literally holding her lover tight. He’s under her thumb. No one has ever doubted who painted this because only one artist could.

The Last Supper (1490-97/98)

Photograph: Associated Press

Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

The most documented of all Leonardo’s works is also the most damaged and difficult to interpret. He used experimental methods on a damp wall and it started to fall to pieces the moment he put down his brush. Over the centuries it was repainted and repainted until a radical restoration in the late 20th century tried to remove every bit of added paint to recover the “pure” touch of Leonardo. It was a quixotic돈키호테식 quest추구追求 that has left this great painting a pixellated ruin. What we can know, what is undeniably real, are the dramatic composition, eloquent무언無言의 웅변 gestures and deep theatrical perspective with which Leonardo presents this tragic moment. We see betrayal, fear, horror and the certainty of death in a scene that totally reinvented the art of storytelling. Cinema starts here.

The Virgin of the Rocks (2nd version) (1491-99 and 1506-08)

Photograph: Print Collector/Getty Images

National Gallery, London

Leonardo’s first attempt at this painting was so heretical이단異端 and odd that he had to paint it all over again. In this second version, he conforms to orthodoxy by giving John the Baptist a cross to show his premonition예감 of Christ’s fate, and removing the angel’s finger that pointed at John. Yet this is not as purely his work at the original was. Only one detail – the incredibly beautiful and startlingly androgynous중성 angel with the ringlets he loved in boys – is definitely by him. After a recent restoration, the National Gallery has claimed it all or mostly his work, but that is totally unconvincing. The difference between the careful but slightly flat execution of most of it, and that fantastic angel makes it clear that he let assistants finish it. Even so, this is the greatest painting in the National Gallery.

Portrait of a Woman (La Belle Ferroniere) (1493-94)

Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Louvre, Paris

More elusive종잡기 어려운, and a bit more ordinary than Leonardo’s other female portraits, this painting nevertheless has his subtle미묘 feel for character, as well as showing his unique ability to flesh out살을 붙이다 a face in smooth curves and shaded features. She’s very solid and very alive. Her mysterious personality – is she a lover of the Duke of Milan, is she communicating disdain경멸? – adds to the painting’s understated yet undeniably Leonardoesque sense of human psychology.

Salvator Mundi (1499 onwards)

Photograph: Reuters

Private collection

If this painting, which has just sold for the world record price of $450m (£341m), looks fake, that’s because it is a religious masterpiece painted by an atheist. It is a genuine Leonardo but not a genuine expression of his thoughts and feelings. That insincerity saps it of soul그림에서 영혼을 없애다 even as it spooks겁먹게 하다 you with the illusion of Christ’s presence. You have to see this strange unlovable work of genius in a gallery, face to face, to appreciate its power. However much it has been reworked over the centuries – as all old paintings have – there is something special and potent about it that puts it in a different league from any work by Leonardo’s imitators. In 2011, the National Gallery included it in the exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan. That boosted this forgotten painting into the limelight and kickstarted the process that has culminated in the sale of the century. Was the National duped속이다 into helping to authenticate a dodgy의심스러운 picture? Not a bit of it. The less than perfect condition of this eerie괴상한 icon was obvious, but so was its bizarre brilliance. It holds a room in a very odd and disconcerting way. Christ’s steady gaze is unsettling, uncomfortable, frightening.

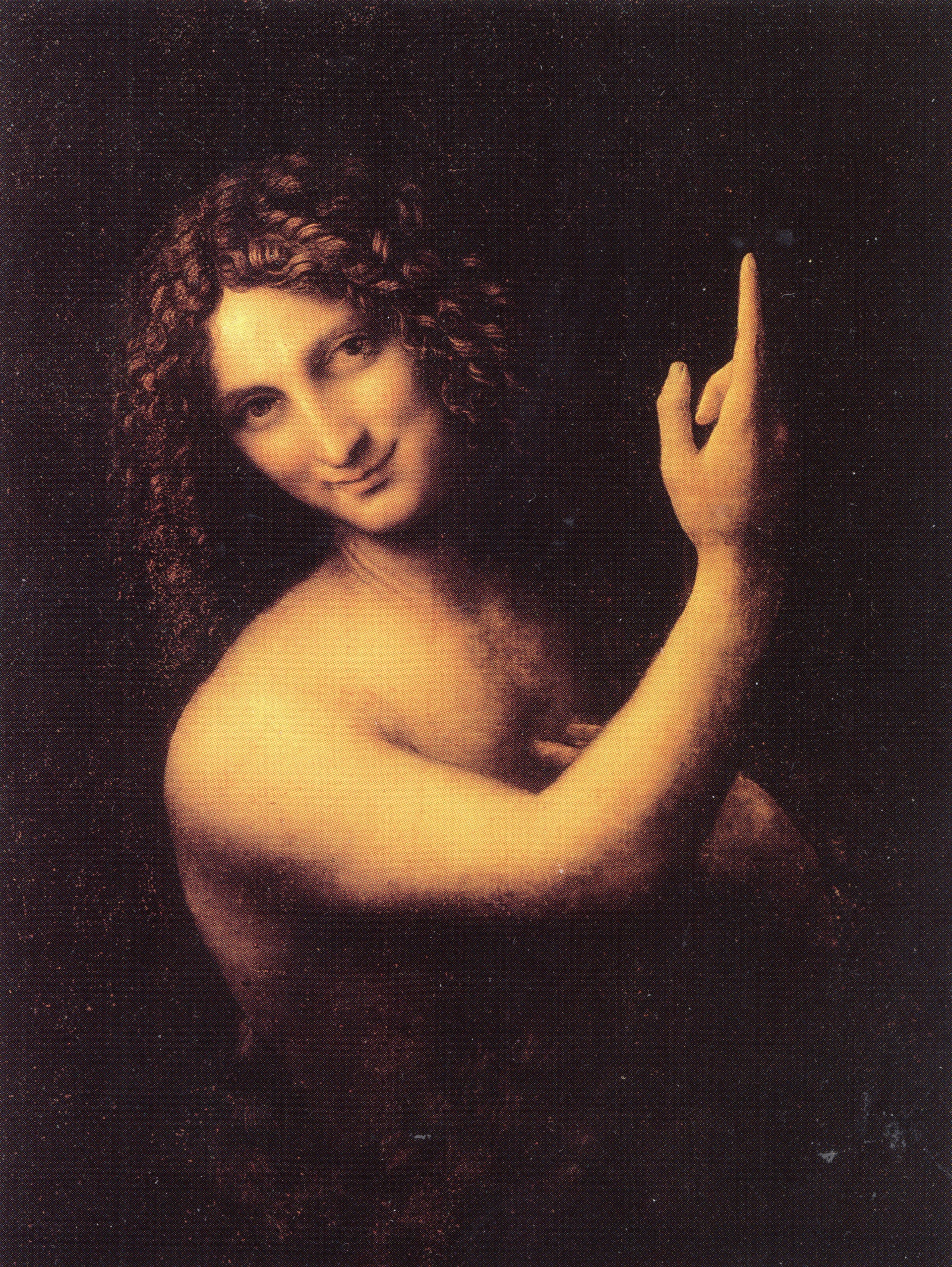

Saint John the Baptist (1500 onwards)

Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Louvre, Paris

Leonardo’s obsession집착 with John, the patron saint of Florence, reaches its culmination in this homoerotic portrait of the Baptist as a beautiful youth. The way he raises his finger to heaven may seem sacred, yet a drawing survives in which either Leonardo or one of his pupils (could it be his mischievous짖꿎은 protege제자 Salai?) gives this same image a huge erection. The similarity to his erect finger suggests Leonardo and the lads in his workshop joked that the finger was phallic. The supremely rich, glowing light and ethereal가녀린 nudity of this painting play deliberately on the sacred and profane불경不敬: was John the Baptist, for Leonardo, a gay hero whose friendship with Christ he imagined as heretically carnal색정色情?

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (1501 onwards)

Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Louvre, Paris

Perhaps Leonardo’s greatest painting. Its blue dream of mountains in the distance is so vast and infinite, while the details of rocks in the foreground are directly rooted in his scientific studies of nature. Leonardo collected fossils and knew what they were. In this painting, he shows not just an eye for nature but a deep knowledge of it. The way the landscape encompasses에워싸다 the holy family makes it a painting of the vastness and grandeur of nature and the mystery of life. There is something profoundly satisfying about its misty air and infinite distances.

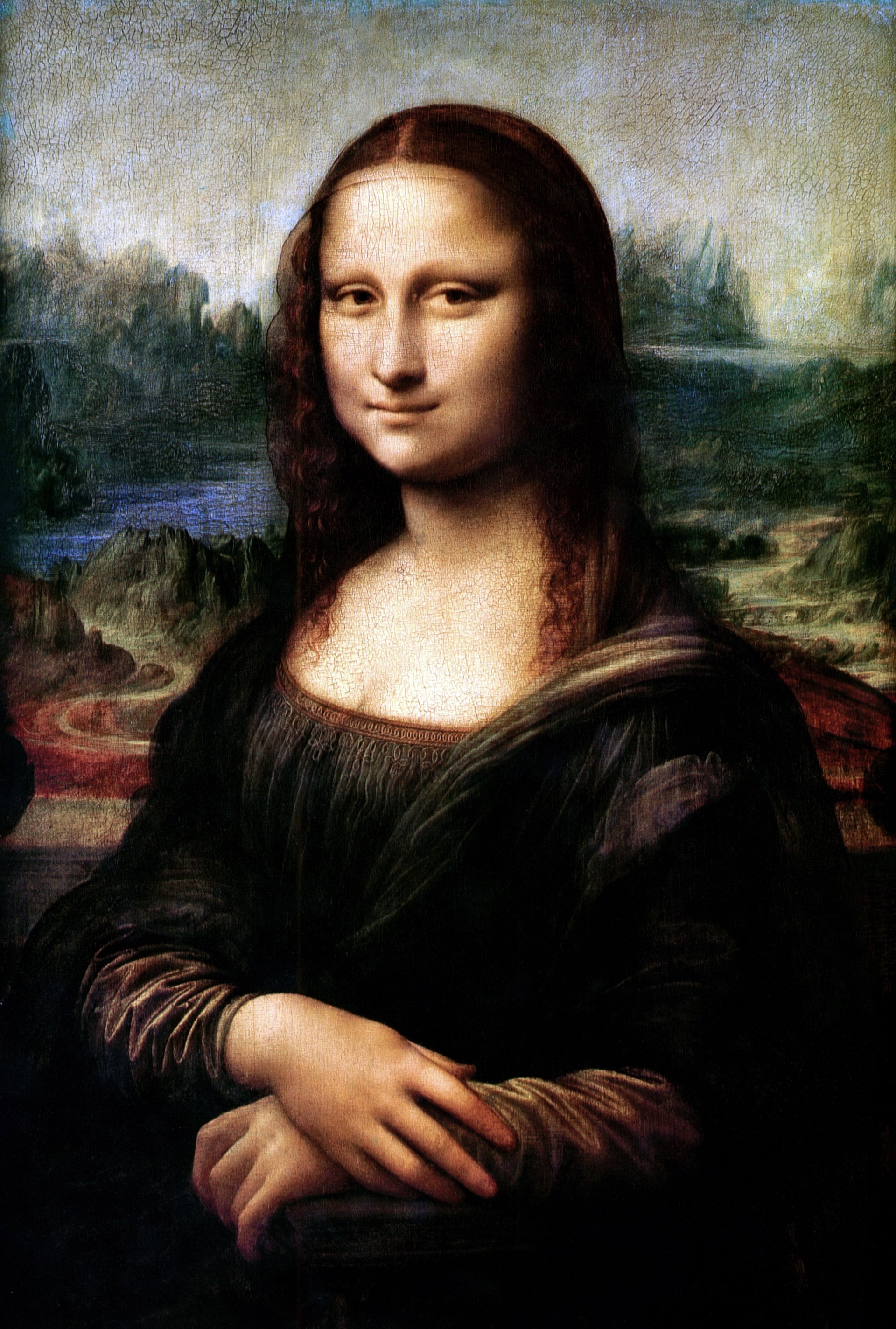

The Mona Lisa (1503 onwards)

Photograph: History Archive/Rex Shutterstock

Louvre, Paris

No painting causes more controversy, yet the facts are simple. A document discovered a few years ago in Heidelberg University library reveals that Leonardo started his portrait of Lisa, the wife of a Florentine silk merchant, in 1503. Scientific studies reveal she wasn’t actually smiling. Out of this straightforward commission, he created his most enigmatic불가사의 masterpiece of all. Everything from the half-smile he artfully imposed on her to the long and winding road behind her adds to the sense of a hidden meaning, a secret life. This is the culmination of Leonardo’s love of women. A Florentine merchant’s wife did not have as much freedom as the confident court women of Milan. Instead, he finds the Mona Lisa’s freedom within her, by giving her a dreamlike quality and a dark sense of undisclosed knowledge. Her secretive smile seduces for ever.