- 1 History

- 2 Building and library features

- 3 Library Services

- 3.1 Main Library

- 3.2 Specialized libraries

- 3.2.1 Taha Hussein Library for the Blind and Visually Impaired

- 3.2.2 Nobel Section

- 3.3 Museums

- 3.3.1 Antiquities Museum

- 3.3.2 Manuscript Museum

- 3.3.3 Sadat Museum

- 3.3.4 History of Science

- 3.4 Permanent Exhibitions

- 3.5 CULTURAMA

- 3.6 VISTA

- 4 Management

- 5 Post-Revolutionary Involvement

- 6 Criticism

- 7 Gallery

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 Further reading

- 11 External links

[edit] History

Mediterranean side of library

Inside Bibliotheca Alexandrina

Mirror of the Internet Archive in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina

The idea of reviving the old library dates back to 1974, when a committee set up by Alexandria University selected a plot of land for its new library, between the campus and the seafront, close to where the ancient library once stood. The notion of recreating the ancient library was soon enthusiastically adopted by other individuals and agencies. One leading supporter of the project was former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak; UNESCO was also quick to embrace the concept of endowing the Mediterranean region with a center of cultural and scientific excellence. An architectural design competition, organized by UNESCO in 1988 to choose a design worthy of the site and its heritage, was won by Snøhetta, a Norwegian architectural office, from among more than 1,400 entries. At a conference held in 1990 in Aswan, the first pledges of funding for the project were made: USD $65 million, mostly from the Arab states. Construction work began in 1995 and, after some USD $220 million had been spent, the complex was officially inaugurated on October 16, 2002.[1]

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina is trilingual, containing books in Arabic, English and French. In 2010, the library received a generous donation of 500,000 books from the National Library of France, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF). The gift makes the Bibliotheca Alexandrina the sixth-largest Francophone library in the world. The BA also is now the largest depository of French books in the Arab world, surpassing those of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, in addition to being the main French library in Africa.[2]

[edit] Building and library features

The dimensions of the project are vast: the library has shelf space for eight million books, with the main reading room covering 70,000 m² on eleven cascading levels. The complex also houses a conference center; specialized libraries for maps, multimedia, the blind and visually impaired, young people, and for children; four museums; four art galleries for temporary exhibitions; 15 permanent exhibitions; a planetarium; and a manuscript restoration laboratory. The library's architecture is equally striking. The main reading room stands beneath a 32-meter-high glass-panelled roof, tilted out toward the sea like a sundial, and measuring some 160 m in diameter. The walls are of gray Aswan granite, carved with characters from 120 different human scripts.

The collections at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina were donated from all over the world. The Spanish donated documents that detailed their period of Moorish rule. The French also donated, giving the library documents dealing with the building of the Suez Canal.

Bibliotheca Alexandrina maintains the only copy and external backup of the Internet Archive.

[edit] Library Services

The library provides access to print on demand books via the Espresso Book Machine.[3]

[edit] Main Library

[1]

[edit] Specialized libraries

[edit] Taha Hussein Library for the Blind and Visually Impaired

The Taha Hussein Library contains materials for the blind and visually impaired using special software that makes it possible for readers to read books and journals. It is named after Taha Hussein, the Egyptian poet and literary critic and one of the leading figures of the Arab Renaissance (Nahda) in literature, who was himself blinded at the age of three.

[edit] Nobel Section

Contains book collections of Nobel Prize Laureates in Literature from 1901 to present. The Nobel Section was inaugurated by Queen Silvia of Sweden and Queen Sonja of Norway on 24 April 2002.

Nobel Section

[edit] Museums

[edit] Antiquities Museum

[edit] Manuscript Museum

|

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2010) |

[edit] Sadat Museum

[2] This museum contains many different personnel belongings of the Egyptian president Anwar Al Sadat. This includes some of his military robes,the noble prize medal, his copy of the Quraan, some letters written by him, some pictures of him and his family and the blood stained military robe he wore in his assassination. The museum also contains a recording in his voice of a part of the Quraan and different newspaper editions featuring him.

[edit] History of Science

See History of science

[edit] Permanent Exhibitions

[edit] The World of Shadi Abdel Salam Exhibition

The World of Shadi Abdel Salam exhibit contains many of the works and effects of the Egyptian film director, screenwriter, and costume designer Shadi Abdel Salam, donated by his family to the Library to put on permanent display. This includes his personal library, some of his furniture, several awards, and many storyboard paintings and costumes from several of his films.

[edit] CULTURAMA

The culturama hall consists of a huge 180-degree panoramic interactive computer screen with a diameter of 10 meters that is made up of nine separate flat screens arranged in a semicircle and nine video projectors controlled by a single computer. Culturama has enabled the display of information that could never have been displayed clearly using a regular computer display system.[4]

It was developed by the Egyptian Center for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage (CULTNAT) and holds its patent in 2007.

It displayed 3 periods from the history of Egypt:

- Ancient Egyptian Period

- Highlights of Islamic Civilization

- Modern Egypt

Virtual Immersive Science and Technology Applications. It uses CAVE Technology. VISTA features several projects including

- BA Model: A complete virtual recreation of the BA including the Library’s main building, planetarium, study rooms, and even the Library’s furniture will be seen clearly and accurately in this demo.

- Sphinx

- Socio-Economic Data Visualization: A new visualization technique for multi-dimensional numerical data. The case study uses data provided by the UN, including health care, life duration expectancy and literacy rate over a 25 year period in some countries.

[edit] Management

The current director is Ismail Serageldin. He also chairs the Boards of Directors for each of the BA's affiliated research institutes and museums and is a professor at Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

[edit] Post-Revolutionary Involvement

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina held a variety of symposiums in 2011 in support of the Egyptian community and emphasizing the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, the Egyptian Constitution and Democratic Government in Arab nations. The library also displays a photo gallery of the January 25, 2011 revolution and is working to document it in a wide variety of formats.[5]

[edit] Criticism

Criticism of the library comes chiefly from two angles. Many allege that the library is a white elephant impossible for modern Egypt to sustain, and serves as little more than a vanity project for the Egyptian government. Furthermore, there are fears that censorship, long the bane of Egyptian academia, would affect the library's collection.[6] In addition, the building's elaborate architecture (which imitates a rising Sun) upset some who believed too much money was being spent on construction rather than the library's actual collection. Due to the lack of available funds, the library had only 500,000 books in 2002, low compared to other national libraries. (However, in 2010 the library received an additional 500,000 books from the Bibliothèque nationale de France.) It has been estimated that it will take 80 years to fill the library to capacity at the current level of funding. The library relies heavily on donations to buy books for its collections.[7]

[edit] Gallery

| The building |

|

|

|

An ancient statue in front of the library |

|

|

|

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina Pool, adjacent to the library outer wall. |

|

|

|

The BA Pool with the Mediterranean Sea on the background. An artistic statue is in view |

|

| Antiquities Museum |

|

|

|

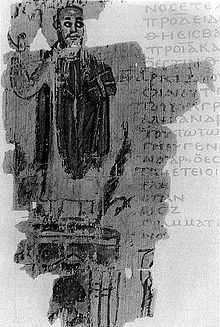

Ancient drawing found in excavations under the new Alexandria library |

|

|

|

Two burial artifacts taking the face of a monkey and a jackal. |

|

|

A view on an old version of a Quran manuscript |

|

|

Old window with inscriptions from the Quran | |

|